Only in English

The Winter Palace

Update Required To play the media you will need to either update your browser to a recent version or update your Flash plugin.

The Winter Palace is a vast baroque residence, having 1057 rooms, 117 staircases and more than 2000 windows. The palace we see today is the fifth to stand on the spot – its four predecessors survive only in historical records. Empress Elizaveta Petrovna gave the commission for the original palace to the Italian architect Francesco Bartolomeo Rastrelli. However, she did not live to see its completion, and Rastrelli's work on the new palace was inherited by the new Tsar, Peter III.

The opening ceremony nearly became a fiasco – the workers had used the whole of Palace Square as a building yard, and it was covered in piles of bricks, barrels of lime, rubble, timber, and logs. The day was saved by a wily Chief Of Police. He put out an announcement to all citizens of the city, that they could come along and help themselves to anything that took their fancy – and for free. Within twenty-four hours the whole square had been stripped clean of anything that could be lifted.

A fearful blaze in December 1837 swept the Winter Palace, entirely destroying the external decorations. The conflagration had begun in a chimney-flue, from whence the flames spread into the attic. The palace furnishings perished almost completely in the blaze, but servants managed to save most of the royal possessions. Old masters, marble figures, clocks, mirrors, and bronzes were all piled up on Palace Square around the Alexander сolumn. Yet amazingly there wasn't a single case of looting reported, and during the entire period of fire the only items reported missing were a silver coffee-pot and a gold ornament belonging to Her Majesty. And in fact both these items subsequently turned up when the snow melted on the Square later.

Fifteen months to the day after the great fire, the Winter Palace was reopened in all its splendour. It proved impossible to recreate Rastrelli's baroque interiors, and thus most of the rooms of the palace were arranged anew, in the newly-fashionable classical style.

The Winter Palace was the scene of another dramatic incident on the 5th of February 1880 – an assassination attempt on the Emperor's life, the fifth attempt in a row. The would-be assassin gained employment at the palace as a cabinet-maker, and used this identity to smuggle some forty kilograms of dynamite into the Royal dining-room. The floor and walls were entirely blown-out by the strength of the blast, but the Emperor avoided injury by lucky chance.

It was from the balcony of the Winter Palace in 1914 that Tsar Nicholas II announced the outbreak of hostilities by which Russia became enmeshed in the First World War. When military action began the Winter Palace was converted entirely into a hospital for the wounded, whilst remaining a royal residence in name only until 1917. After Tsar Nicholas II abdicated in February 1917 the Winter Palace became the official headquarters of the new Provisional Government. The former Royal residence had become home to its own replacement.

Yet just a few months later, on the night of the 25th and 26th October 1917, soldiers and sailors entered the Winter Palace and arrested the government ministers of the Provisional Government in the White Dining-Room. A myth began later – greatly aided by soviet-era film-making – that the palace had been stormed by Bolsheviks. In fact, no such storm ever took place. The guard on the Winter Palace was made up by the Ladies Battalion and cadets from military schools – who put up no resistance whatsoever.

The Winter Palace was in a sorry state after it was ceded – the floors were strewn with books and some of the pictures were torn. Luckily the art collections of the Provisional Government were redistributed soon after, and mostly sent to Moscow, to the Kremlin.

The Winter Palace complex today provides the exhibition space for the State Hermitage Museum. The number of objects in the collection is so great that it would take 8 years to spend just one minute on each. It therefore makes good sense to preplan your visit to the Hermitage collections and decide in advance what you most want to see – the Royal staterooms, the Italian Renaissance collection, the Rembrandts, the Scythian Gold Treasury, and so forth.

The New Hermitage was Russia's first purpose-built museum building. You can see it at the northern end of Millionaya Street – a strict classical-style building with a large portico in the centre of its facade. The roof of the portico is held aloft on the shoulders of Atlantean statues, carved from dark granite.

The portico, with its atlantean statues supporting the roof, was the main entrance to the New Hermitage from its opening until 1917. Today, however, access is via the Winter Palace only.

During the bombardment of WW2 one of the atlantes of the portico was damaged – a lump of German shrapnel pierced his granite torso. Petersburgers have a superstition that the recipe for a happy marriage lies in coming to rub the feet of the atlantes on the day before the wedding.

The opening ceremony nearly became a fiasco – the workers had used the whole of Palace Square as a building yard, and it was covered in piles of bricks, barrels of lime, rubble, timber, and logs. The day was saved by a wily Chief Of Police. He put out an announcement to all citizens of the city, that they could come along and help themselves to anything that took their fancy – and for free. Within twenty-four hours the whole square had been stripped clean of anything that could be lifted.

A fearful blaze in December 1837 swept the Winter Palace, entirely destroying the external decorations. The conflagration had begun in a chimney-flue, from whence the flames spread into the attic. The palace furnishings perished almost completely in the blaze, but servants managed to save most of the royal possessions. Old masters, marble figures, clocks, mirrors, and bronzes were all piled up on Palace Square around the Alexander сolumn. Yet amazingly there wasn't a single case of looting reported, and during the entire period of fire the only items reported missing were a silver coffee-pot and a gold ornament belonging to Her Majesty. And in fact both these items subsequently turned up when the snow melted on the Square later.

Fifteen months to the day after the great fire, the Winter Palace was reopened in all its splendour. It proved impossible to recreate Rastrelli's baroque interiors, and thus most of the rooms of the palace were arranged anew, in the newly-fashionable classical style.

The Winter Palace was the scene of another dramatic incident on the 5th of February 1880 – an assassination attempt on the Emperor's life, the fifth attempt in a row. The would-be assassin gained employment at the palace as a cabinet-maker, and used this identity to smuggle some forty kilograms of dynamite into the Royal dining-room. The floor and walls were entirely blown-out by the strength of the blast, but the Emperor avoided injury by lucky chance.

It was from the balcony of the Winter Palace in 1914 that Tsar Nicholas II announced the outbreak of hostilities by which Russia became enmeshed in the First World War. When military action began the Winter Palace was converted entirely into a hospital for the wounded, whilst remaining a royal residence in name only until 1917. After Tsar Nicholas II abdicated in February 1917 the Winter Palace became the official headquarters of the new Provisional Government. The former Royal residence had become home to its own replacement.

Yet just a few months later, on the night of the 25th and 26th October 1917, soldiers and sailors entered the Winter Palace and arrested the government ministers of the Provisional Government in the White Dining-Room. A myth began later – greatly aided by soviet-era film-making – that the palace had been stormed by Bolsheviks. In fact, no such storm ever took place. The guard on the Winter Palace was made up by the Ladies Battalion and cadets from military schools – who put up no resistance whatsoever.

The Winter Palace was in a sorry state after it was ceded – the floors were strewn with books and some of the pictures were torn. Luckily the art collections of the Provisional Government were redistributed soon after, and mostly sent to Moscow, to the Kremlin.

The Winter Palace complex today provides the exhibition space for the State Hermitage Museum. The number of objects in the collection is so great that it would take 8 years to spend just one minute on each. It therefore makes good sense to preplan your visit to the Hermitage collections and decide in advance what you most want to see – the Royal staterooms, the Italian Renaissance collection, the Rembrandts, the Scythian Gold Treasury, and so forth.

The New Hermitage was Russia's first purpose-built museum building. You can see it at the northern end of Millionaya Street – a strict classical-style building with a large portico in the centre of its facade. The roof of the portico is held aloft on the shoulders of Atlantean statues, carved from dark granite.

The portico, with its atlantean statues supporting the roof, was the main entrance to the New Hermitage from its opening until 1917. Today, however, access is via the Winter Palace only.

During the bombardment of WW2 one of the atlantes of the portico was damaged – a lump of German shrapnel pierced his granite torso. Petersburgers have a superstition that the recipe for a happy marriage lies in coming to rub the feet of the atlantes on the day before the wedding.

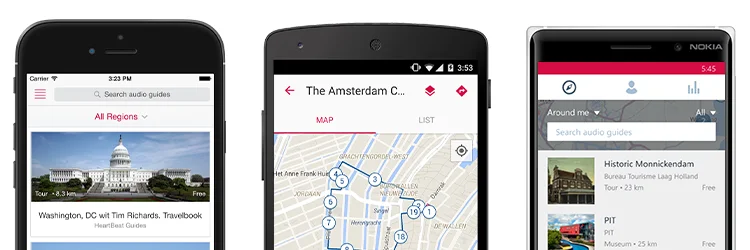

Download the free izi.TRAVEL app

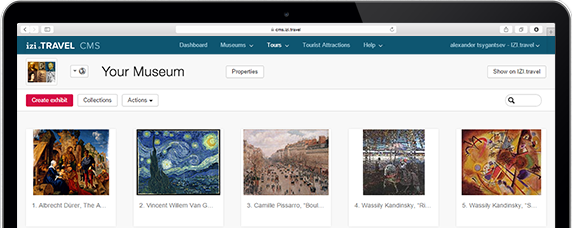

Create your own audio tours!

Use of the system and the mobile guide app is free