The sculptures of the Campanile, circa 1415-36

Update Required To play the media you will need to either update your browser to a recent version or update your Flash plugin.

For the niches of the campanile, the Opera del Duomo ordered a series of sculptures: Kings, Sybils, and Prophets, in other words those figures who prophesied the coming of Christ. The first series was accomplished in the fourteenth century by Andrea Pisano, and presents fluid and elegant draperies, still expressing the Gothic style, together with bodily volume and solidity showing the influence of Giotto. The other statues were commissioned from Donatello during the first half of the fifteenth century, and represent Prophets and Patriarchs: among those entirely by the master, the first to be sculpted are the beardless Prophet (said to be the portrait of the sculptor's friend Brunelleschi) and the bearded Prophet known as “the pensive one.” Be sure to note the realism and vitality of the figures, captured in moments of silent meditation. The prophets Jeremiah and Habbakuk date from twenty years later: it is evident how the always original style of Donatello went through yet another change, with regard to the earlier statues, passing through a progressive accentuation of expressivity that reaches its apex in the extremely modern and tormented Habbakuk.

Let us in fact linger at these two celebrated sculptures: Jeremiah was the prophet of the destruction of Jerusalem, therefore of suffering and of exile. Called the prophet of lamentations, he is shown with his dishevelled attire, and marked by deep wrinles, with the lines of his face contracted in a grimace of sorrow. Donatello enters into the psychology of this character, and reveals all his profound interior suffering.

In contrast, Habakkuk, nicknamed the “Zuccone” or “Pumpkin-head,” is the prophet of curses: the artist presents him as he shouts his pleas and invectives, his thin body consumed by abstinence, his hollowed-out face marked by an intense and tortured expression. It is precisely for this extraordinary realism, for the impression that the statue only needs a voice to come to life, that, as Vasari records, Donatello directly addressed his work, vehemently demanding that he speak. Vasari also reported and gave credence to the popular tradition, fully Florentine in spirit, according to which these prophets are portraits of living contemporaries, defeated adversaries of the Medici: thus the one is disconsolate, while the other is enraged. Even if this claim is uncertain, the two statues' realism does make one think of actual people, modelled directly on living, breathing people who could be seen on the city's streets. These two figures, the last to be carved, were originally placed on the north side of the Campanile, the one closest to the wall of the Duomo, and thus less visible: their beauty, and the great admiration that they inspired, caused the Workers of the Duomo to decide their move to the important west side of the tower, parallel to the facade of the cathedral, in an exchange with the earlier statues by Andrea Pisano. A laborious movement of sculptures, but worth the trouble!

Our itinerary leads us into the Room of the Singing Balconies, Number 23, and then to the Gallery of the Cupola (number 15). The room, which deserves an attentive visit, features models and projects regarding the construction and decoration of one of the greatest achievements of human genius: the Cupola by Brunelleschi.

Let us in fact linger at these two celebrated sculptures: Jeremiah was the prophet of the destruction of Jerusalem, therefore of suffering and of exile. Called the prophet of lamentations, he is shown with his dishevelled attire, and marked by deep wrinles, with the lines of his face contracted in a grimace of sorrow. Donatello enters into the psychology of this character, and reveals all his profound interior suffering.

In contrast, Habakkuk, nicknamed the “Zuccone” or “Pumpkin-head,” is the prophet of curses: the artist presents him as he shouts his pleas and invectives, his thin body consumed by abstinence, his hollowed-out face marked by an intense and tortured expression. It is precisely for this extraordinary realism, for the impression that the statue only needs a voice to come to life, that, as Vasari records, Donatello directly addressed his work, vehemently demanding that he speak. Vasari also reported and gave credence to the popular tradition, fully Florentine in spirit, according to which these prophets are portraits of living contemporaries, defeated adversaries of the Medici: thus the one is disconsolate, while the other is enraged. Even if this claim is uncertain, the two statues' realism does make one think of actual people, modelled directly on living, breathing people who could be seen on the city's streets. These two figures, the last to be carved, were originally placed on the north side of the Campanile, the one closest to the wall of the Duomo, and thus less visible: their beauty, and the great admiration that they inspired, caused the Workers of the Duomo to decide their move to the important west side of the tower, parallel to the facade of the cathedral, in an exchange with the earlier statues by Andrea Pisano. A laborious movement of sculptures, but worth the trouble!

Our itinerary leads us into the Room of the Singing Balconies, Number 23, and then to the Gallery of the Cupola (number 15). The room, which deserves an attentive visit, features models and projects regarding the construction and decoration of one of the greatest achievements of human genius: the Cupola by Brunelleschi.

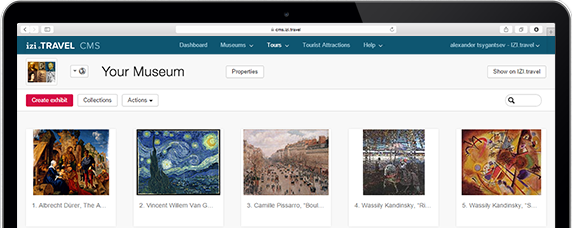

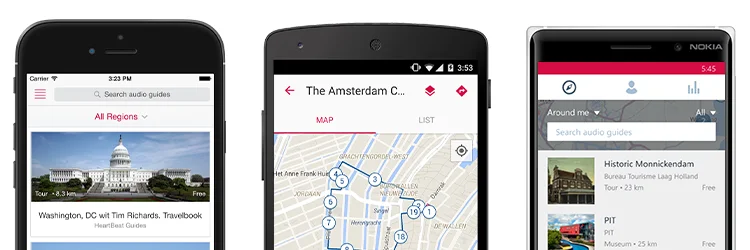

Download the free izi.TRAVEL app

Create your own audio tours!

Use of the system and the mobile guide app is free