Leonardo da Vinci, Annunciazione

Update Required To play the media you will need to either update your browser to a recent version or update your Flash plugin.

Leonardo da Vinci, The Annunciation, 1472-1475 circa, Tempera and oil on panel

Little is known of this artwork, only that it arrived in the Uffizi in 1867 from the Florentine Church of San Bartolomeo: whether it was originally painted for that location, or who the patron was, is not known.

Attribution of the painting to Leonardo is also a fairly recent accomplishment: in the past it was thought that Ghirlandaio, or even Verrocchio, were its creators, but today all agree on ascribing the work to young Leonardo, perhaps the very first work he painted in complete autonomy.

The encounter between the angel and Mary takes place within the unusually elongated panel. The only element shared with the classical fifteenth century representation of the subject is the positioning of the figures: the angel on the left and the Virgin on the right.

The setting is entirely new: until then, the Virgin was always depicted in her room or seated underneath a loggia, never outside as in this painting. The scene in fact takes place in a garden overlooking a vast landscape, a real immersion in nature, which directly takes part in the sacred event. Leonardo tackles nature with the spirit of a scientist, illustrating its variety and beauty through his genius as a painter. Notice how he pays the same attention to painting each component, whether it be a tiny flower on the lawn or the city and mountains in the background, immersed in the haziness of distance.

This is the most important element: from now on, in fact, Leonardo elaborates a new type of perspective, known as “aerial” or “atmospheric”, where the illusion of depth is achieved by employing the “sfumato” technique, that is by reducing contrast: distant objects are paler, less detailed than objects that are near. What does this absolute novelty consist of, this revolution carried out in the birthplace of linear perspective, in the city of Brunelleschi, its creator?

Observe the right hand side of the panel, where the figure of the Virgin is: the scene is constructed through architecture, therefore by using perspective to render the pavement, window, steps and the surface of the lectern.

However, things change in the rest of the painting: the spaces are free and open, without architectural constraints. How, then, does the artist give a sense of distance beyond the foreground? Instead of depicting each object, even the farthest ones, in minute detail as the Flemish did, Leonardo progressively tones down the intensity of the colors: they become paler, while the lines loose their sharpness and precision as the representation moves closer to the horizon. As in real life, the outlines soften and atmosphere envelops bodies of water, the city and mountains. The young artist’s revolution could not have manifested itself in a clearer, more fascinating and imperious way.

A truly beautiful detail: the wings are not the conventional, multi-colored wings of angels, they are instead the wings of a real bird drawn from life, a first clue of the passion for flight that Leonardo pursued throughout his life.

Little is known of this artwork, only that it arrived in the Uffizi in 1867 from the Florentine Church of San Bartolomeo: whether it was originally painted for that location, or who the patron was, is not known.

Attribution of the painting to Leonardo is also a fairly recent accomplishment: in the past it was thought that Ghirlandaio, or even Verrocchio, were its creators, but today all agree on ascribing the work to young Leonardo, perhaps the very first work he painted in complete autonomy.

The encounter between the angel and Mary takes place within the unusually elongated panel. The only element shared with the classical fifteenth century representation of the subject is the positioning of the figures: the angel on the left and the Virgin on the right.

The setting is entirely new: until then, the Virgin was always depicted in her room or seated underneath a loggia, never outside as in this painting. The scene in fact takes place in a garden overlooking a vast landscape, a real immersion in nature, which directly takes part in the sacred event. Leonardo tackles nature with the spirit of a scientist, illustrating its variety and beauty through his genius as a painter. Notice how he pays the same attention to painting each component, whether it be a tiny flower on the lawn or the city and mountains in the background, immersed in the haziness of distance.

This is the most important element: from now on, in fact, Leonardo elaborates a new type of perspective, known as “aerial” or “atmospheric”, where the illusion of depth is achieved by employing the “sfumato” technique, that is by reducing contrast: distant objects are paler, less detailed than objects that are near. What does this absolute novelty consist of, this revolution carried out in the birthplace of linear perspective, in the city of Brunelleschi, its creator?

Observe the right hand side of the panel, where the figure of the Virgin is: the scene is constructed through architecture, therefore by using perspective to render the pavement, window, steps and the surface of the lectern.

However, things change in the rest of the painting: the spaces are free and open, without architectural constraints. How, then, does the artist give a sense of distance beyond the foreground? Instead of depicting each object, even the farthest ones, in minute detail as the Flemish did, Leonardo progressively tones down the intensity of the colors: they become paler, while the lines loose their sharpness and precision as the representation moves closer to the horizon. As in real life, the outlines soften and atmosphere envelops bodies of water, the city and mountains. The young artist’s revolution could not have manifested itself in a clearer, more fascinating and imperious way.

A truly beautiful detail: the wings are not the conventional, multi-colored wings of angels, they are instead the wings of a real bird drawn from life, a first clue of the passion for flight that Leonardo pursued throughout his life.

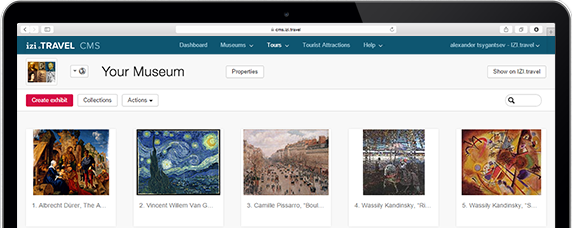

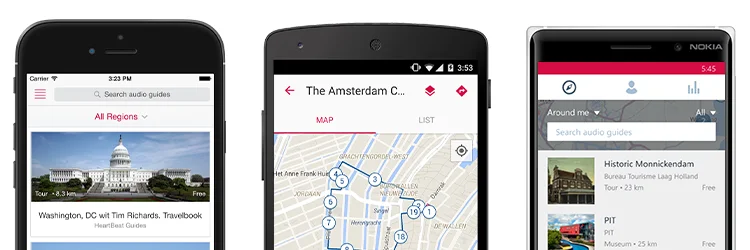

Download the free izi.TRAVEL app

Create your own audio tours!

Use of the system and the mobile guide app is free